Image Credit: JHU Sheridan Libraries/Gado / Contributor / Getty

Image Credit: JHU Sheridan Libraries/Gado / Contributor / Getty Some question if disability accommodations are being abused, but others say there’s a lack of research

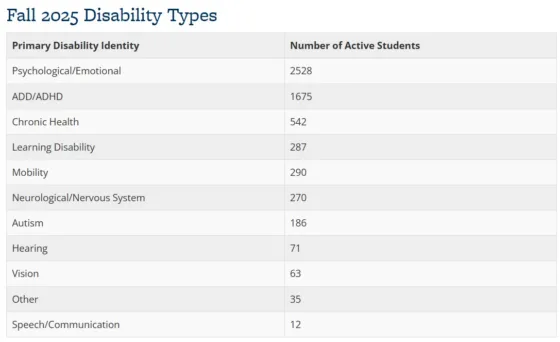

More students are receiving disability accommodations at the University of California at Berkeley this school year, the leading type being for “Psychological/Emotional” disabilities, according to data published on the institution’s website.

The rise in college students receiving disability accommodations nationwide has been under recent scrutiny. However, one expert who spoke with The College Fix pointed out that there is a lack of research on the matter.

At UC Berkeley, this year has the most students registered as disabled since 2020, according to the data.

The data, which only goes back to 2020, shows the number of students who received disability accommodations increasing every year. In 2020-2021, there were 4,153. The following year there were 4,585. This year, there are 5,711.

The greatest percentage of disabled students this year have “psychological” or “emotional” impediments. There are 2,528 registered, representing more than 50 percent of all students with disabilities at the university.

The next most common is ADHD/ADD, with 1,675 students. According to the data, 287 students have a learning disability, 290 face mobility problems, 71 struggle to hear, and 63 have impaired vision.

UC Berkeley’s media relations office declined to comment recently when The College Fix asked how students get accommodations, if it is looking into potential abuses of the system, how the university intends to ensure disabled students’ needs are met amidst the rise of those seeking accommodations, and whether resources are being stretched too thin.

The university did, however, provide links to Berkeley’s Disabled Students Program’s application and FAQs.

Other universities are exhibiting similar trends, prompting questions. A recent opinion piece in The Atlanticshed light on criticism of the issue. For example, at Stanford University, 38 percent of students are registered as disabled, and many students at colleges across the U.S. now receive extra time on exams.

Some accommodations are “uncontroversial, such as universities outfitting buildings with ramps and providing course materials in braille,” according to The Atlantic. However, others have prompted questions about abuses, such as one California university student who received permission to bring their mother to class.

Last week, The Fix spoke to Alvin Christian, a predoctoral research fellow at the University of Michigan, who recently published the paper, “Academic Accommodation in Higher Education: Patterns, Predictors, and Potential.” He is studying economics and public policy.

For his study, Christian said he looked at “transcripts, disability office records, and K–12 special education histories” to “examine growth, gaps in use, and the effects of accommodations.”

He found that “usage has risen sharply.” Christian said that “between 2011 and 2024, the share of students approved for accommodations more than doubled from 4% to 10% … and that growth is accompanied by accommodations for mental health diagnoses in college, which quadrupled during this time period.”

His study also discovered that, “Men and Asian students are half as likely to use accommodations (relative to women and white students, respectively).”

Financial class is another distinguisher as “low-income and high-income students are more likely to use [accommodations] compared to their middle-income peers.”

However, Christian told The Fix, “These gaps are not due to underlying differences in disability rates across these groups (proxying for disability with K-12 disability status), and is instead driven by application behavior.”

Christian also looked at the effects of accommodations, finding that “accommodations yield substantial benefits. Approved students withdraw from fewer courses, earn higher GPAs, persist longer, and are more likely to major in STEM.”

Regarding the equitable distribution of resources for disabled students, Christian said: “In the ideal world, disability would be a binary condition that we observe for everyone. Then, schools could effectively target supports. In reality, disability is on a spectrum and we only observe disability status for students who come forward to seek accommodations.”

“What my research shows is rapid growth in accommodations associated with mental health conditions, which often involve lower barriers to diagnosis than learning disabilities like dyslexia,” he told The Fix.

“That raises questions about whether existing accommodation frameworks – many of which were designed around physical or learning disabilities – are well matched to students’ needs today,” he added.

However, the researcher made it clear he was not speaking against accommodations for mental health.

“I want to be careful not to imply that students with mental health conditions do not deserve accommodations. However, this does raise some uncomfortable questions about fit,” he wrote.

“Are we providing the right kinds of supports for different students? In my data, nearly all students who receive accommodations are given testing-related supports. It is not obvious that these are always the most appropriate response; for example, does extended test time meaningfully address challenges related to anxiety or depression?” Christian said.

When asked whether the rise in qualifying disabled students has any repercussions on resource availability, the researcher told The Fix he did not have data on it.

However, “as usage rises, institutions face tradeoffs: staffing disability offices, ensuring timely evaluations, and maintaining consistent standards.”

Regarding how universities can ensure disabled students receive adequate accommodations while preventing others from abusing the system, Christian offered a few solutions: “more stringent documentation requirements and recency standards, limits on how long approvals last before re-evaluation,” and “more stringent eligibility rules for specific diagnoses or accommodations.”

He also recommended “requiring in-house or affiliated medical professionals for evaluation or approval (to prevent shopping around).”

However, Christian also said that all his recommendations have “tradeoffs because they may reduce take-up overall, but disproportionately affect less advantaged students.”

The College Fix also recently spoke to Richard Allegra with the Association on Higher Education and Disability about the rise in disability accommodations.

AHEAD is the “leading professional membership association for individuals committed to equity for disabled individuals in higher education,” according to its website.

When The Fix asked whether accommodations were being given too freely and if there are potential repercussions linked to the rise in those seeking them, Allegra pointed out the lack of data on the matter.

“Unfortunately we’re not able to address these questions because there aren’t any data that we’re aware of that have studied ‘abuse’ of disability accommodations,” Allegra said. “I did a search on those terms in the ERIC database and couldn’t find any myself.”

However, there is ample research showing “students not receiving adequate accommodations due to campus ableism or resources, or students failing to disclose disabilities due to continuing stigma about disability,” he told The Fix.

“Given the current anti-DEI climate more needs to [be] reported about disabled students receiving individualized accommodations and campus obligations around accessibility under federal laws that are still in effect,” Allegra said.