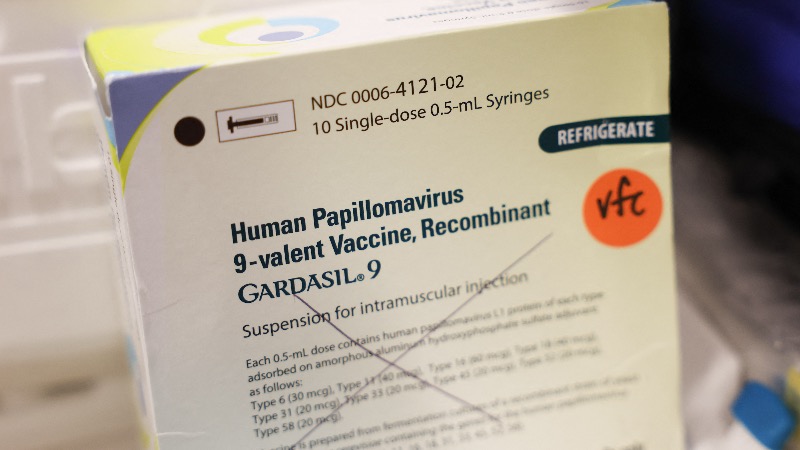

Image Credit: PATRICK T. FALLON / Contributor / Getty

Image Credit: PATRICK T. FALLON / Contributor / Getty After nearly two decades on the childhood immunization schedule, the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine is undergoing a formal reassessment.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has convened a new workgroup to re-examine the vaccine from the ground up — its effectiveness, dosing, safety and long-term population impact.

The workgroup will be led by Massachusetts Institute of Technology Professor Retsef Levi, a current ACIP member who has consistently pressed for longer safety follow-up and greater transparency about uncertainty in vaccine science.

For much of the past 20 years, ACIP’s approach to HPV vaccination followed a trajectory of expanding eligibility, strengthening uptake and adding new indications.

Once licensed, the core assumptions underpinning the policy were rarely reopened.

That approach now appears to be shifting.

A reassessment long deferred

In December 2025, the CDC updated its website to publish new Terms of Reference, directing the new workgroup to reassess the cumulative evidence after almost two decades of real-world use.

That task is expected to draw on expertise spanning multiple fields, including clinical medicine, epidemiology and population health.

Levi said the review begins from the recognition that cervical cancer remains a serious disease and that HPV infection is a major risk factor.

He noted that “the HPV vaccines together with screening programs, and education to responsible sexual behavior are all inter-related public policies attempting to limit the incidence, prevalence and impact of cervical cancer.”

Levi also pointed to ACIP’s own policies and procedures, which state that each vaccine recommended by the committee should be comprehensively reviewed at least every seven years.

“Accordingly,” he said, “the HPV workgroup intends to conduct a comprehensive review of the published and unpublished scientific and clinical knowledge regarding the current evidence and uncertainties with respect to the benefits and risks of the vaccine.”

He added that the workgroup is now recruiting highly qualified experts, with the aim of applying evidence-based analysis and open inquiry in preparation for a robust discussion among ACIP members.

Strain replacement back on the agenda

According to the Terms of Reference, the workgroup is tasked with examining type-specific HPV infection trends over time.

What those trends show has been the subject of ongoing debate in the scientific literature.

The original HPV vaccines targeted the most common cancer-associated strains, particularly HPV-16 and HPV-18, and subsequent population-level studies reported declines in those vaccine-targeted strains.

However, some studies have reported relative increases in other oncogenic HPV strains not covered by the original vaccines, raising the possibility that suppressing dominant strains may allow others to fill the ecological space.

A Finnish population study, for example, observed declines in HPV-16 and HPV-18 alongside increases in strains such as HPV-52 and HPV-66.

Concerns about incomplete strain coverage drove the development of Gardasil 9, which expanded protection from four to nine HPV types.

But broader coverage has not necessarily translated into better outcomes.

In a Merck-sponsored study of more than 14,000 women, Gardasil 9 did not reduce high-grade cervical lesions compared with the original quadrivalent vaccine — despite targeting five additional strains.

In short, covering more strains did not result in fewer serious pre-cancers overall.

How many doses?

The Terms of Reference instruct the workgroup to examine evidence on HPV vaccination schedules with fewer doses, including how the dose number affects effectiveness, durability of protection and long-term population outcomes.

However, U.S. federal health authorities have since overhauled the childhood immunization schedule, reducing HPV vaccination to a single routine dose.

That shift reframes the workgroup’s task, placing greater emphasis on assessing how well existing evidence translates across different populations, including how durable protection is and whether immunity wanes.

Safety questions resurface

The most striking shift is how safety is now being treated.

The Terms of Reference direct the workgroup to examine post-marketing safety evidence in depth — including adverse-event reports by dose and timing, data from the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) and findings from both clinical trials and observational studies.

They also instruct the group to scrutinize “the potential toxicity of HPV vaccine, adjuvants, and potential contaminants and/or impurities.”

In my reporting, one longstanding concern that has emerged is that most pre-licensure trials used Merck’s proprietary aluminium adjuvant, AAHS, as the placebo, limiting the ability to generate clean comparative safety data.

Another unresolved issue I have examined is residual DNA contamination detected in the Gardasil HPV vaccine.

Regulators have repeatedly said the levels present pose no risk, but that conclusion rests largely on theoretical thresholds rather than direct human safety studies.

To date, no clinical trials have specifically tested the safety of residual DNA in these products — a gap that now falls squarely within the scope of the workgroup’s review.

This renewed focus comes against the backdrop of litigation over alleged Gardasil-related injuries, which has intensified scrutiny of how safety signals were assessed and how uncertainties were communicated after approval.

Weighing benefits and harms

The HPV vaccine is unique in that any anticipated benefit — reducing cervical cancer — lies decades in the future. By contrast, if a serious adverse effect does occur, the resulting injury would appear much sooner and could be lifelong.

That timing imbalance is why the benefit-harm trade-off when vaccinating healthy adolescents now sits squarely before the workgroup.

The new Terms of Reference state that the work of this group may lead to ACIP recommendations being “revised or withdrawn” if new evidence emerges.

For a vaccine long treated as untouchable, that language matters.

With nearly 20 years of data now available, ACIP is fulfilling its charter and taking a second look — this time with fewer assumptions and a lot more questions.